Bone Stress Injuries in Youth Athletes

Bone stress injuries (BSIs) are a growing concern affecting up to 19% of youth athletes with recurrence rates of as high as 21%. BSIs are overuse injuries especially affecting those involved in high-impact, endurance, aesthetic or weight category sports. These injuries can cause significant time loss taking youth athletes out of sport participation for many months, therefore proactive prevention and early detection can have a huge impact on long term athletic development and career trajectory. As youth sports become increasingly competitive, understanding, preventing, and treating BSIs is essential to keeping young athletes healthy and active.

What are Bone Stress Injuries?

A bone stress injury is a spectrum of bone damage caused by repetitive mechanical loading that exceeds the bone's capacity to recover. This can range from a mild stress reaction with inflammation (oedema) within the bone (early-stage) to a partial or complete stress fracture.

Bone stress injuries can be more common during rates of rapid growth which put adolescent athletes at a higher risk. Also, as energy demands are higher during these years unintentional under fuelling can be common, contributing to low bone mineral density and further vulnerability.

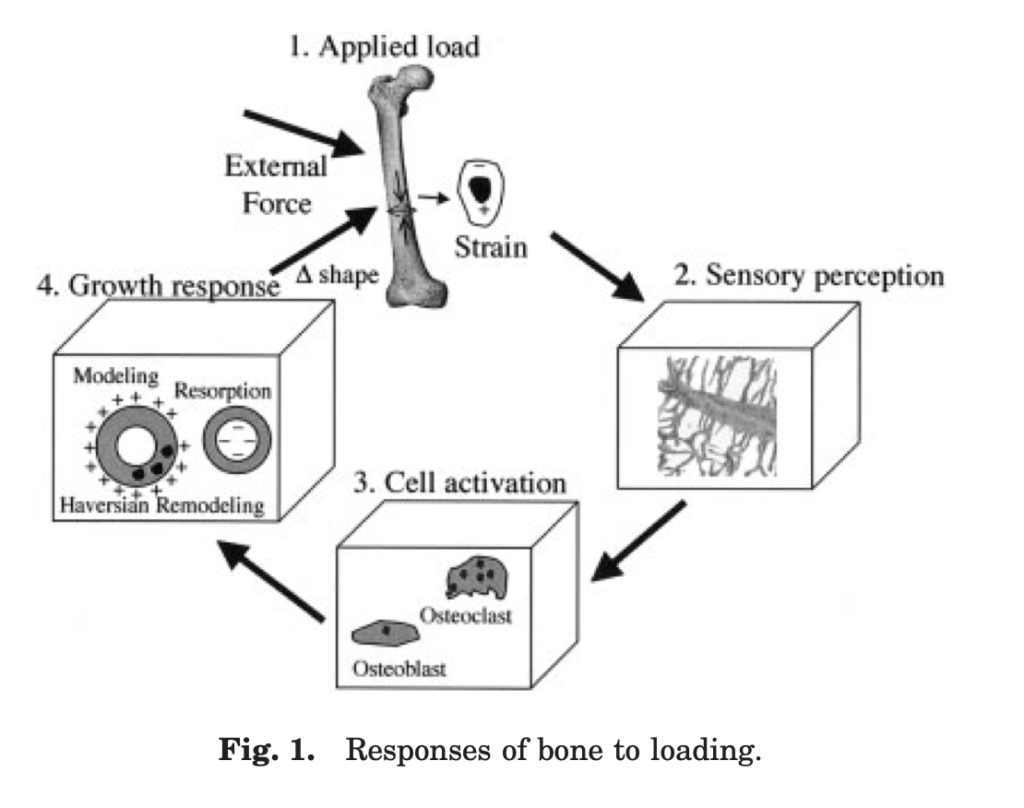

How do they happen?

Bones are mechanically loaded during movement and adapt to become denser when subjected to increased intensity of loading during activity such as jumping and lifting heavy weights. This phenomenon (Wolff’s Law) allows bone tissue to withstand the demands of sporting activity going through a process of resorption before laying down new, stronger bone. However, if bones are repeatedly subjected to force without adequate time or resources to recover, the positive adaptations are lost, and continued resorption leads to weaker and more vulnerable bones. In youth athletes, this is often caused by overtraining from intense sports schedules, under fuelling or lack of recovery time.

How are bone stress injuries diagnosed?

BSIs tend to be painful, worsening with activity and improving with rest. Pain is often localised to a specific bony area but can sometimes present more like wider spread muscular pain. Pain can be felt during the night or in the morning. Bone stress injuries are best detected by MRI as they can take a few weeks to show up via xray.

Common sites for bone stress injuries in youth athletes are the leg, foot and ankle, lumbar spine and pelvis. These will often correlate with the demands of the sport, for example leg and foot BSIs can be common in basketball players and endurance runners who experience a large volume of jumping and landings, and lumbar spine BSIs in cricketers, gymnasts and dancers who perform repetitive spinal extension and rotation.

Why do we call them bone stress injuries?

The term "bone stress injury" reflects the progressive nature of the damage - starting with stress and inflammation in the bone before developing into a more serious fracture. Using this terminology emphasises early detection and intervention to prevent long-term consequences.

Contributing Factors to BSI

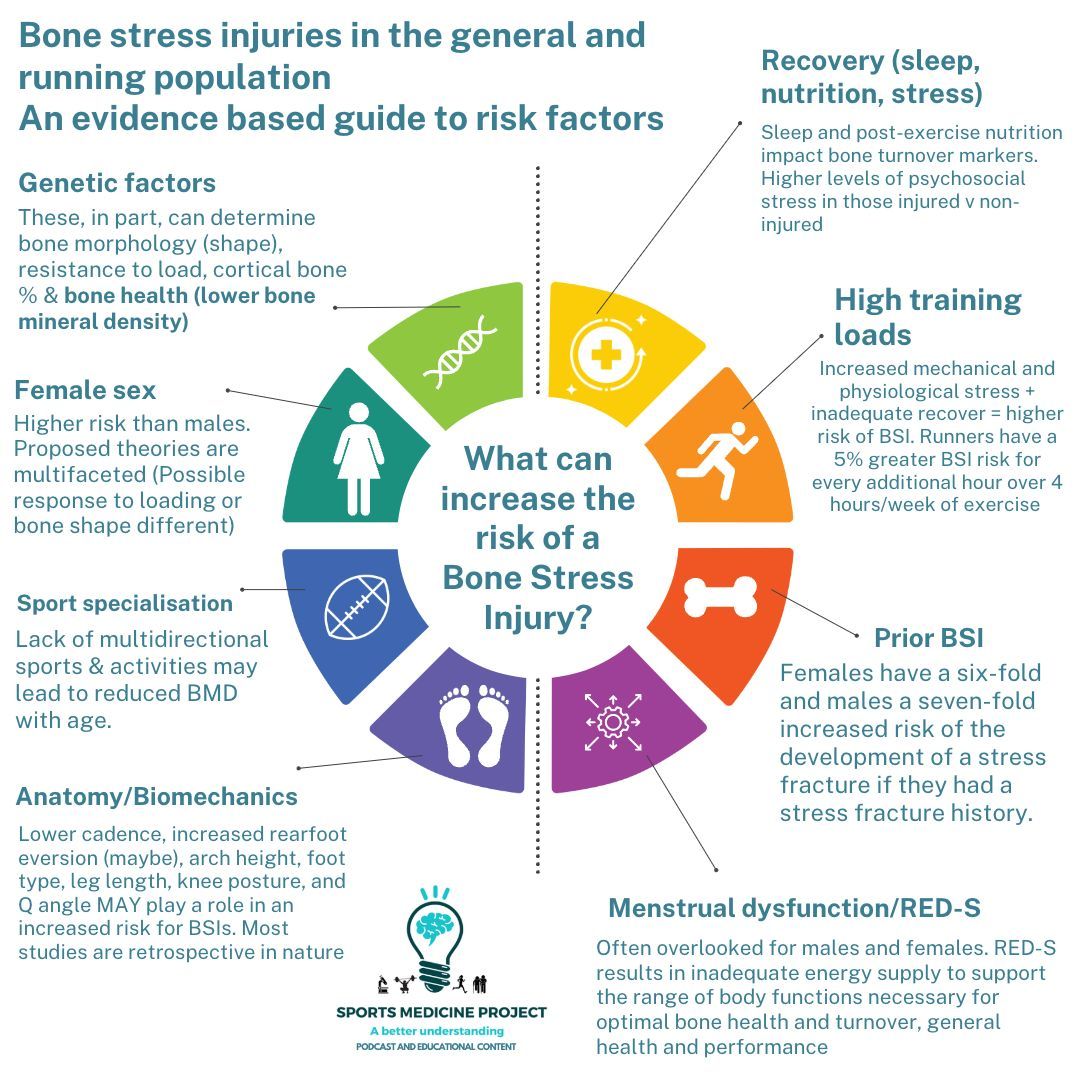

A combination of physical and physiological factors can increase the risk of developing a bone stress injury in young athletes:

Overtraining: Excessive training without suffieicient rest overloads bones and limits recovery.

Nutrition: Inadequate calorie intake or poor nutritional choices can compromise bone health. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) is a commonly used framework for describing the consequences of low energy availability (consuming less calories than required for bodily functions, activity level and growth).

Bone Mineral Density (BMD): Low BMD weakens bone structure, making it more vulnerable to stress. Deficiencies in Vitamin D and Calcium are especially linked to weakened bones.

Hormonal Factors: Menstrual irregularities in female athletes or low testosterone in males can impair bone development. This can often be as a result of RED-S as ‘non-essential’ body systems are downregulated in a state of low energy availability.

Rapid Growth: Growth spurts can temporarily reduce bone strength and coordination, increasing injury risk.

What’s the Treatment for a Bone Stress Injury?

Treating a BSI requires patience and a comprehensive recovery plan:

Recovery Timeline: Most BSIs take 6 to 12 weeks to fully heal, depending on severity and location.

Offloading: Removing stress from the affected bone often through rest, modified activity, or supportive devices such as boots and crutches is essential for recovery.

Appropriate bony loading: As previously mentioned, bones like loading and require these forces to adapt and strengthen. Carefully managed and progressive loading is a key part of the mid to late-stage rehabilitation for bone stress injuries. Ensure you are working with an experienced Strength and Conditioning Coach or Physiotherapist who will guide you through an appropriate programme based on bone healing timeframes and the severity of the injury.

Don’t forget the rest of your body: Bone stress injuries can have you out of action for a while, so maintaining strength and fitness in the rest of the body is important for your athletic development. You can still train other areas whilst resting your injured site.

Getting on top of contributing factors: Managing underlying conditions such as RED-S, overtraining, and vitamin deficiencies will help to increase bone mineral density and support healing.

After Return to sport: What to Expect

Even after the bone has healed, bone mineral density can take 12 to 18 months to return to normal levels. If the underlying causes such as poor nutrition or overtraining aren’t addressed, recovery may take even longer and risk of re-injury increases, not only at the original injury site but in other areas as well.

How to Prevent Bone Stress Injuries

Prevention is the best treatment. Here are key strategies to protect youth athletes:

Manage Training Load: Ensure at least one full day off per week from structured training. Try to plan breaks between training sessions. Research has shown that leaving longer rest periods between training bouts ie. morning and evening training sessions with rest in-between, is optimal for bone health and allows for better adaptation.

Diversify Training: Avoid early specialisation; cross-training by participating in a variety of sports builds balanced strength and coordination. Strength and Conditioning can play an important role here for athletes who have specialised early.

Plan Nutrition: Prioritise nutrient-rich, balanced meals and ensure adequate caloric intake for activity levels. Ensure you are fuelling and refuelling before, in-between and after training sessions with carbohydrate rich snacks.

Prioritise Rest and Recovery: Recovery is just as important as training in building strong bones. Prioritise your sleep, ensuring you get between 8-12 hours per night.

Monitor Growth: Be especially vigilant during growth spurts, inform your coaches if you are growing fast and adjust training accordingly.

Encourage Open Communication: Early reporting of pain or discomfort can prevent a minor issue from becoming a major injury.

Conclusion

Bone stress injuries are preventable with the right balance of training, nutrition, and recovery. By fostering awareness and supporting youth athletes with holistic care, we can help them stay healthy, happy, and performing at their best.

Resources

Project RED-S: Your go-to site to learn more about low energy availability and it’s repercussions for youth athletes: https://red-s.com/

Performance Canteen: Personalised nutrition support for the growing athlete: https://performancecanteen.co.uk/

Move4Sport: Experienced coaches specialising in youth athletic development available for 1-1 and group rehabilitation sessions: https://www.move4sport.com/

References

Armento, A., Heronemus, M., Truong, D. and Swanson, C.,2023. Bone health in young athletes: a narrative review of the recentliterature. Current osteoporosis reports, 21(4), pp.447-458.

Beck, B. and Drysdale, L., 2021. Risk factors, diagnosis andmanagement of bone stress injuries in adolescent athletes: a narrative review.Sports, 9(4), p.52.

Hoenig, T., Ackerman, K.E., Beck, B.R., Bouxsein, M.L.,Burr, D.B., Hollander, K., Popp, K.L., Rolvien, T., Tenforde, A.S. and Warden,S.J., 2022. Bone stress injuries. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 8(1), p.26.

Mountjoy, M., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Burke, L., Ackerman, K.E.,Blauwet, C., Constantini, N., Lebrun, C., Lundy, B., Melin, A., Meyer, N. andSherman, R., 2018. International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement onrelative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. International journalof sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 28(4), pp.316-331.

Ohta-Fukushima, M., Mutoh, Y., Takasugi, S., Iwata, H. andIshii, S., 2002. Characteristics of stress fractures in young athletes under 20years. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 42(2), p.198.

%20(1).jpg)